Still-lives - & a life gone still

Spirit of daughter lives on in Elaine Fasula's paintings

by Paul Smart

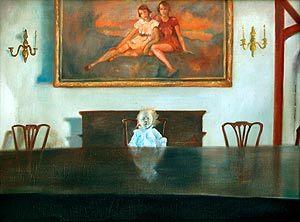

Elaine Fasula's Artist in Residence, 40x30.

There are a half-dozen paintings on the walls of Elaine Fasula's Shokan home that are among her earliest creations: large, classically styled pieces featuring a young girl glimpsed across a deep dining table beneath a painting of two teen girls; asleep beneath an open window, a realistic toy-sized dinosaur at her side; or standing before a bay, in a hooded shroud, looking haunted. Around them are several still-lives, a couple of more conventional portraits and a lot of blank space that the artist is explaining is not the room's natural state. She's having a show in New York's SoHo neighborhood, she says.

Then Fasula adds that the works with the girl are not for sale. They're old, she starts saying; early pieces, not as accomplished as what she's been making recently. And more importantly - they're personal. She can't part with them. They have a story and a meaning that fuel everything she does, in both her art and life.

There's something simultaneously richly painted and thinly executed, deeply imagined and yet conceptually familiar about much of what Elaine Fasula makes. There's an enthusiasm to the work matched by an engaging darkness. Yet there are also elements of a not-quite-mature tendency to finish before a painting gains the sort of obsessive detail that great art enjoys, as well as a barely definable naïveté. You rarely see work of this neo-Baroque sort in the marketplace, unless it's driven by some Modernist concept.

I'm thinking about the recent exhibit of Julie Heffernan's wild self-portraits of herself as a Marie Antoinette-sort on fire, or as a swarm of fireflies captured against the ceiling of some Rococo palace room. Or Norwegian painter Odd Nerdrum, who overcame the limitations of his old-school talents and interests with extreme craftsmanship (making his own pigments!) and the creation of a smartass "school" for critics to see his work through - which he labels "the return of Kitsch."

None of that for Fasula, whom we met at a recent afternoon concert put together by her friend and neighbor, composer George Tsontakis, to celebrate her completion of a portrait of him made as a thank-you for his having given her son, an avid piano student, a home piano on which to practice. The soiree featured wine and cheese, recitals and much talk - and several dozen of Fasula's artworks on the walls of Tsontakis' fabulous home overlooking the Ashokan. Four, she says, were sold to the gathered crowd. Then another sold the week following to a walk-in customer down in the city street-level loft that she rents from a friend for exhibit purposes each year. "I just love being there, watching the gallery and listening to people discuss my paintings, not knowing I'm the painter listening in," she says.

Her prices range between $600 and $6,500 a painting. Last year she sold 11 during her week in New York. The piece she sold recently went for $6,000.

"I have always wanted to paint," she starts explaining, talking about how she'd used the medium as part of a business that she built up years ago making accessories for film cameras. But she also used it as a means of enlivening her dream of making a subtle political statement: that beauty is necessary, and a counterpoint to much that is ugly in the world.

Fourteen years ago, Fasula said, there had been a great tragedy in her life. Gypsy, her 9-year-old daughter with noted highwire artist Philippe Petit, died suddenly of a cerebral aneurysm. "The last thing I said to her was that I'd paint her," she says of what had been a hobby of sorts before then, a dream: something she observed her friends and partners of many years doing as she picked up what she liked, what felt right to her, somewhere deep inside.

"I started writing and painting her. It wasn't work I wanted to sell because it was so personal. And I wanted to feel stronger as a painter first," she says of the pieces built from dreams, collected into a book that she still works on, keeping Gypsy's memory alive. "But then when I moved up here I decided to start painting full-time."

For the past seven years, Fasula says, she's been honing her talents - painting daily, learning to simulate some of her favorite effects from the art of the 17th and 18th century. Getting her chops in order, as it were.

She took some work out to galleries in New York on occasion, but learned two lessons in the process: first, that what she was doing didn't quite fit what was out there, even when those rejecting it couldn't explain themselves. And secondly, that marketing oneself as an artist is a full-time job in itself. She wanted to paint, not shape her art to the idea of sales.

"I realized I couldn't really change my direction, and didn't want to," she says, mentioning how she was invited into a number of galleries where one pays to show one's work - an equation that she didn't feel was serious. "I'm still hopeful, especially when I listen in on people I don't know talking about my work, or a painting sells to someone walking in from the street and falling in love with what I do."

So how did she get from paintings about her daughter, and her own battle to accommodate her grief over Gypsy's death, to the current still-lives? And how has her style improved over the years?

Fasula talks about painting direct to canvas; about spending days in her studio never getting out of her pajamas, working through ideas until they feel right. She points out the odd aspects of her still-lives, surreal in their quiet way, and how "they take me elsewhere"; and how she loves working with those elements of her craft that she finds most challenging. As a result, Fasula says, she feels that she's just getting better and better as a painter - which makes up for her lack of success in the selling world, like so many we meet who build their lives as artists.

She prides herself on the speed with which she often works - "getting it right" in a matter of hours, say - or the fact that she's sold 45 paintings to date. And yet she wishes she could support herself from her art. And she wishes deeply for the validation of commercial success giving the nod of approval to all she's been putting on canvas of herself.

"Still-lives are studies that stimulate the imagination," she writes. "With each image, one is able to feel a powerful radiance, along with the shadow that runs beneath radiance: a study of life."

"I can never imagine myself not painting," she says of what drives her. "I like that I'm still learning, still getting there."

We are looking around her works and somehow come back to the paintings that she did years ago of Gypsy: those works she won't part with, but that seem to have this extra power, this incredible depth of emotion in each brushstroke. And we don't say anything. I'm wishing Fasula could get back to these pieces, even if they're not as accomplished, in 17th-century style, as much of what she's done since. And then the artist speaks.

"I had other dreams of Gypsy," she said, telling of having met her departed daughter years later, with her new son on hand. And the girl had grown up and was playing violin in the streets of lower Manhattan. And she painted her - just as, no matter how many works she keeps private or gets out into the world, she will now always be painting her.

Source: Ulsterpublishing.com (11/22/06)